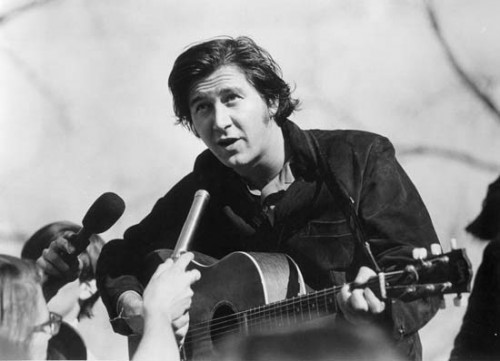

West Texas was a place of suffering during the Great Depression. A Jewish doctor of Polish descent arrived there with his wife in 1938, after being sent from New Jersey by his employer, the United States Army. Jacob and Gertrude Ochs settled in El Paso, where their son Phil was born into a world about to go to war in December of 1940.

Phil would become a tremendous influence, a tragic figure, and later, a forgotten man,

Raised in the 1940s and 1950s, he was an admirer of John Wayne and World War II hero-turned-actor Audie Murphy (as well as James Dean), and as a boy seemed to accept a lot of the notions that Wayne and Murphy stood for. At 16, Ochs chose to attend Staunton Military Academy in Virginia. He lived the life of a cadet successfully for two years before entering Ohio State University in 1958. Music had already begun to attract him, and he’d developed an interest in country music, which later helped provide his introduction to folk music. It was while at Ohio State that he was introduced to the songs of Woody Guthrie, Lee Hays, and Pete Seeger, and the protest tradition they represented. He bought a guitar for $6 and taught himself to play it in his spare time.

By the end of the 1950s, Phil was leading protests on campus against mandatory ROTC training. Ochs moved from Ohio to New York in the early ’60s and was soon a prolific writer of the protest songs then in vogue. His initial recording efforts were heard on compilations for Broadside, Folkways, and Vanguard (which recorded him at the Newport Folk Festival).

A songwriter and singer who was cast in the Woody Guthrie and Pete Seegar mold, Phil spent his career in the shadow of Bob Dylan. Unlike Dylan, who remained aloof regarding the social issues of the time, Phil was a true believer, dedicated to making the world a better place through the power of music. He believed in the causes he sang about, and this may have been his downfall. Phil considered himself to be a journalist whose medium was that of song. He used his gift to tell stories that were relevant and important.

In contrast to Dylan, who was an enigmatic media star after 1964 – Ochs assumed the role of outlaw, writing and performing songs that told the unvarnished truth. His sincere voice made every word count, and he made his meaning quite clear.

In “Here’s To The State Of Mississippi” he tackles racism and violence:

And here’s to the cops of Mississippi

They’re chewing their tobacco as they lock the prison door

Their bellies bounce inside them when they knock you to the floor

No they don’t like taking prisoners in their private little war

Behind their broken badges there are murderers and more.”

In “The Cannons Of Christianity” Phil took on religious hypocrisy.

His anti-war songs were the best ever written, including “I Ain’t Marching Anymore”, “Chaplain Of The War”, and many others.

His songs about the justice system showed a deep insight into the social problems lurking there, including ideas that only became a subject for serious discussion many years later, like false confessions, the subject of “The Confession” – the first verse of which says:

There’s nothing as cold as the freeze in your soul at the moment when you are arrested.

There’s nothing as real as the iron and steel on the handcuffs when you protested.

You race through the night in a prison of fright as you head for a quicksand of questions.

And children unborn will see you in scorn if ever you make a confession.

Ochs moved many to a fresh round of tears about President Kennedy with “Crucifixion.”

Because his lyrics were controversial, and contained open references to such taboos as smoking marijuana, his recordings were relegated to “undergound” radio stations and counterculture record shops. But for all of his outlaw reputation – which began coalescing around him as early as 1965 in some establishment circles – his work ended up infiltrating high school classrooms through the songs “The Highwayman” and “The Bells” the latter an extraordinarily early intersection between folk song and art song. Eventually he too would follow Dylan into electric music and more personal and romantic compositions.

But Ochs had something extra, even in those years: Street credibility among the people who cared – where Dylan, due to his own various personal situations, spent much of the late ’60s as an enigmatic recluse, respected for his songs but rather unknowable and remote.

Ochs was in Chicago for the 1968 Democratic National Convention, when thousands of young citizens (supported by a few brave politicians) took to the streets to scream “Enough!” about the Vietnam War, and were brutally suppressed by the police under orders from the city’s mayor. He even ended up as a witness at the subsequent conspiracy trial of the seven alleged conspirators behind the demonstration. And no matter how far his style advanced, and how complex his songwriting became, he never abandoned his involvement with the issues he believed in.

Apart from American involvement in the Vietnam War, which dragged on into the mid-’70s, he saw many of the causes that he cared about move toward some measure of fulfillment as the 1970s dawned; but personal problems, including clinical depression and alcoholism, left him drained, psychologically and musically.

By the middle of the decade he found there was nothing left inside, and he finally died by his own hand in 1976. It was only after his tragic tailspin and eventual death that he was properly appreciated as one of the most sincere and humane songwriters of his day, whether detailing political atrocities or more poetic concerns. As the decades have passed, he has been largely forgotten, but in his era, Phil Ochs was one of the most influential of American songwriters.